The European Foundation Conference this year was held in Sarajevo, 15-17 May 2014. It was entitled “Rethinking Europe: Solidarity, civil society and political governance”. Why was the conference held in Sarajevo? Erik Rudeng, The Chair of European Foundation Centre said that: “Sarajevo provides a very special location, in relation to the centenary anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, allowing us to take a critical look at the past, discuss issues affecting communities across Europe today and look to the future and the role of foundations in building and sustaining vigorous and peaceful societies within Europe and worldwide”.

As the representative of Foundations for Peace (FFP) Network in this conference, I participated in a session entitled, “Beyond the logframe, philantrophy in contested and fragile societies” a theme I felt was very relevant to the overall context of the conference. In our session, which was attended by arround 50 participants from several countries, I shared the experience of FFP members who are indigenous foundations working with conflict and peacebuilding issues in different parts of the world, including Sri Lanka, Georgia, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Colombia, Northern Ireland, Palestine, Serbia, Israel and Indonesia.

The need to discuss this issue came from our shared experiences at FFP which has shown that using the Logical Framework Analysis in fragile and constested societies is very problematic. Our experiences have taught us that funding for peacebuilding work in fragile societies requires a much more patient and nuanced approach to funding and evaluation. Some of the realities in our contexts include unbalanced power relationships wherin any challenge to status quo is subversive and violent confrontations. Our work usually follows a trajectory where we take one step forward and two steps backwards. We need to be extremely sensitive to time and nuance and need to engage with multiple stakeholders.

Our experience has taught us the need to raise critical questions while giving grants and these include:

- Will your initiative generate tensions or build bridges?

- Will beneficiaries be spesifically targeted because of the project?

- Will the initiative sse violence or genuine dialogue and participation?

- Will it create safe spaces?

- Will it bring forward social justice and human rights issues?

- Is it disproportionate?

While on the other hand, , the Logical Framework Approach (LFA) poses some obvious limitations in our contexts. First of all, as Nobuka Fujita (2010) in the Foundation for Advanced Studies on International Development research report[1], points out, let us look at the key charcteristics of the LFA.

- LFA was initially designed as a military planning approach for a context of strong central.

- If well-designed, logical frameworks can provide a convenient, simple overview of the main features of an intervention

- LFA reflects a management style, which demands precisely structured and quantifiable objectives.

According to Gasper (2000), there are three recurrent failings/dilemmas of applying the LFA, a simple tool, to a complex reality:

- Logic-less frames are invented to justify an existing project design, e.g. when institutional donor funding is sought for an on-going activity.

- Lack-frame over-simplifies, omitting vital aspects of a project as it ties activities and objectives into a linear cause-to-effect chain.

- Lock-frame blocks learning and adaptation to new opportunities and risks

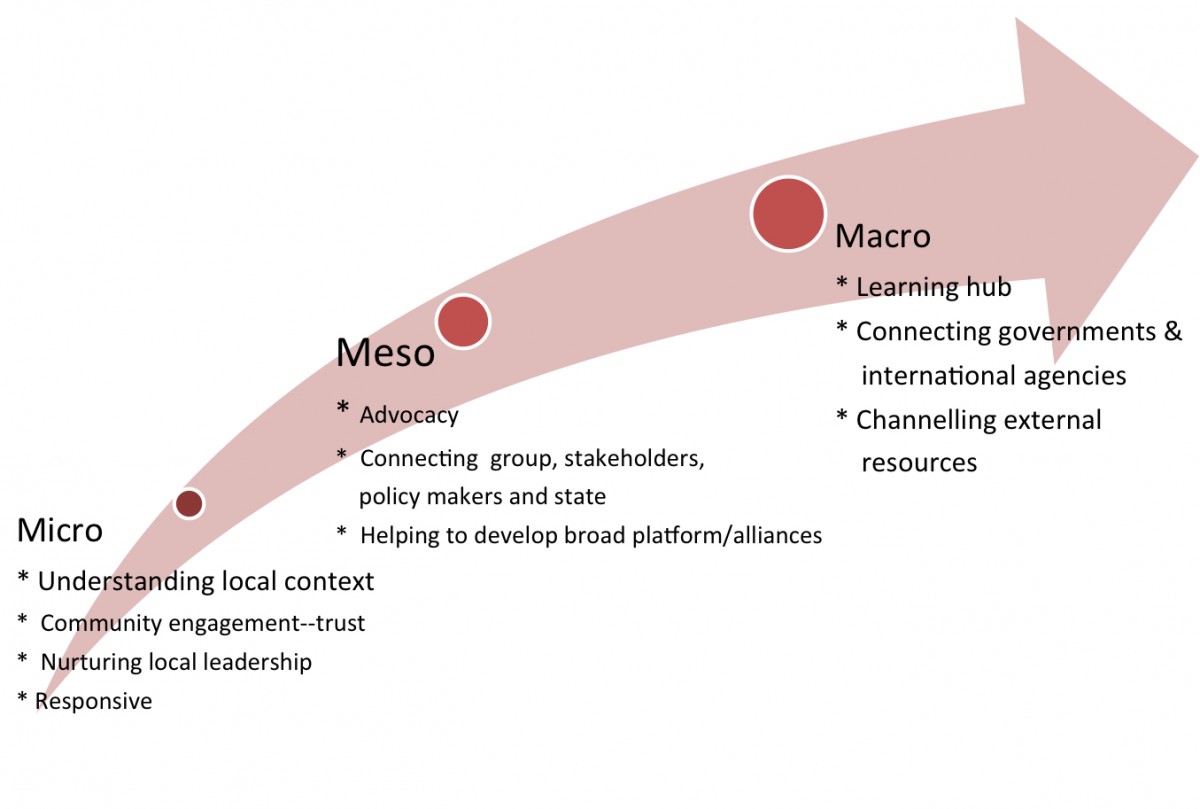

At FFP we beleive that looking beyond the logical framework is critical to the work of indigenous foundations that are based in contested and fragile societies. As a network, FFP offres a different kind of legitimacy, evidence of effectiveness and a means of support and sharing. Given our local nature, particular structure and contextual metodologies, we beleive that independent indigenous foundations can play strategic roles in peace building work, with small money achieve big impact. To understand several best practices of FFP members, below are some example that you can explore further on our websites:

Careful analysis to understand local context

- The provision of water to a camp for IDPs and local community (The Abraham Fund-Israel/ www.abrahamfund.org)

- Supporting family members that had been victims of disappearances/detained by military or armed groups (Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust-Srilanka/ www.manusherjonno.org)

- The important role of women in mediating a divided society (Taso Women’s Fund-Georgia/ www.taso.org)

Creating space for community engagement

- Providing educational programme for children in local language (the Manusher Jonno Foundation- Bangladesh/ www.manusherjonno.org)

- The use of arts to develop a positive identity of Dalits community (the Dalit Foundation-India /www.dalitfoundation.org )

- A cross-community group of Hindu and Muslim women took strong action to prevent violence (Nirnaya Women Fund-India/ www.nirnaya.org)

- The importance of lobbying and campaigning (Tewa Fund-Nepal/ www.tewa.org

Seeking added value dimensions that should complement grantmaking

- Share ideas and approaches for conflic transformation/International Restorative Justice conference, 2005 (Alvar Alice Foundation-Colombia/www.alvaralice.org)

- Importance of external-internal philantropic partnership approaches (Community Foundation for Northern Ireland/www.communityfoundationni.org)

Ensuring accountability and transparency

- Womens participation in monitoring and evaluation (the Dalia Foundation-Palestine/www.dalia.ps)

Diversity in board, staff and project supported

- Flexible general support that enables groups to have more freedom, creativity and innovation (The Reconstruction Women’s Fund-Serbia/ www.rwfund.org)

Allowing space for flexibility and reciprocity

- Supporting human rights defenders and their family (Indonesia for Humanity/ www.ysik.org)

Below is a graph that sums up the strategic roles and added value of indigenous foundations:

Ratna Fitriani is Programme Director at Indonesia for Humanity and a member of the Foundations for Peace Network.

[1] Fujita, Nobuko. Beyond Logframe; Using Systems Concept in Evaluation, Foundation for Advanced on International Development, Japan, 2010.